J. J. French

Storyteller

Bloodlines 2

They should have called it Vampire: The Masquerade - Nomad.

It's pretty good.

It is not at all an RPG, despite borrowing the trappings. It has a lot in common in with Batman: Arkham Aslyum: lots of actually pretty good story moments enriched by outstanding performances, plenty of pretty-but-shallow exploring, lots of beating up/chewing on baddies, and plenty of time menacing Seattle's back alleys and rooftops. This is lightweight "action-adventure" soaked in vampire vibes. And the vibes are perfectly delivered. Voice-in-your-head Fabien is precious, smart-assed glue that provides a ready foil to just about every possible thing the story and world have to offer, and the cast of steady characters never disappoints. The feel of sweeping around the city as a menacing, annoyed, immortal investigator is spot-on. The narrative ranges from "I'm pretty sure I remember this episode of Angel" to delicious Witcher 3-class twists and turns. It's worth the price of admission.

From what I can tell, it's remarkable that this game shipped at all. I'm not privy to the real story, but what I gleaned is that this game started development at one team (going under the moniker Hardsuit Labs), then went into purgatory after the Hardsuit team ran into trouble, and was then handed to another team, The Chinese Room. My guess is that given the budget, time, and expertise available, the game that shipped is essentially a wholly-new adventure bolted (by the second team) into a shell created by the first team. There are oddities lurking in the experience, little rough edges where you step out of richly conceptualized moments into annoyingly forced fights or the liminal streets that thread through Seattle, as the game gives you something to do while conveying the adventure from one (heart)beat to the next. Given a concept of "Winding, layered mystery with bitey-slashy action", well, the overall package works OK. Kudos to The Chinese Room for getting something together and out the door in decent shape.

My main criticism is that there's good enough world and story here that I actually do want the extra depth of a proper "immersive sim" RPG. It's one of those games where the yearning ache of "what this could have been" is very strong. But it is what it is, and what there is, is good.

New tune - Limerent Flow

https://jerion.bandcamp.com/track/limerent-flow

This one revisits a few ideas I've had in past work, and just spends a little more time with them. It's nice to make something just because your creative muscles crave it, and for no other reason whatsoever.

Virtual photography

This is an infrequent hobby of mine. From 2017 to 2019 I was trying to break into the game industry as a lighting artist. Ultimately the junior-level job opportunities that did come my way in that career path simply did not pay enough to cover my rent, so I took a different, more corporate path when it came to making a living. But during that push I needed the beginnings of a portfolio, and those beginnings turned from something I did to get a job into something I did just because it was fun. A game engine like Unreal, with its multitude of lighting, FX, and rendering features, makes for a pretty solid workstation app for this sort of thing. In effect I'm putting together a slice of a game environment, or perhaps more accurately a game cinematic environment, minus the game itself. However, working in a game engine, which is inherently geared for interactive play, means dealing with a multitude of shortcuts that make it possible to show a new image, or frame, of a game on your screen at least 30 times in 1 second, rather than doing things "properly" and showing 1 new frame every 30 seconds. Games are carefully orchestrated piles of cheats, hacks, shortcuts, and duct tape, and the best-made ones deftly embrace that fact. Lighting artistry is no exception.

"Night Rider", October 2018 - Baked lighting. The shadows and shot composition are doing most of the work here.

Just a handful of years ago the standard method of lighting a game environment was to fake hyper-detailed illumination by doing an offline calculation (called 'building lighting') to 'bake' a pretty accurate picture (called a 'lightmap') of light and shadow into each surface of the world. Baked lighting was essentially unchangeable without being rebuilt, so if you wanted interactivity with your lights (such as a working light switch or a flashlight), game engines would provide various mechanisms for dynamic lighting and shadowing. Dynamic lights (and the shadows they create) would be able to move, change in brightness or color, and be used for interactive gameplay in combination with baked lighting, but were relatively intensive, so you rarely saw lots of them used at the same time. All of these lights, both baked and dynamic, came from deliberately placed 'light actors' that you'd put into the game world kind of near to whatever prop was meant to be the source of the light. If, for example, you had a nice generic fluorescent ceiling light in your game world, in order to make it behave realistically you'd have the model of the light fixture, and then an invisible light source floating around or in front of it to send light out into the world.

Along the way, GI - or 'Global Illumination' - systems would work out how the light from those hand-placed sources in your world should bounce around a bit, and try to give it that extra little bit of realism. GI systems help a lot with letting light naturally and compellingly spill through a room and covering up the shortcuts you need to take in the name of expediency. As an artist you probably wouldn't bother adding a unique light source for every LED on a piece of tech, and just leave that kind of detail out, because rebuilding lighting took ages. It was slow. So the less artistic stuff there was in your scene for you to fine-tune, the faster your project could go. All of this is to say that in those recent-enough days, lighting in games was both extremely deliberate and extremely inflexible.

"1:53 AM", May 2020 - Baked lighting. Not the most focused scene, but carefully calibrated to hint at parts of the world you can't see.

But light in the real world doesn't really work that way. In the real world, light is accidental, comes from a multitude of sources big and small. And for the last couple years, the newest versions of Unreal Engine have included a very different approach to lighting, which the engine's developers at Epic Games call Lumen. Lumen is one of a new breed of light-rendering systems - often you'll see this kind of thing advertised as ray tracing, and usually it is or is closely related - that behave rather like those used in TV and film (think Pixar's RenderMan). That means that all the rules for how you put light into a game scene are wildly different now. Systems like Lumen don't treat light as something that's painted into every surface of the world; they instead treat light as something that comes from and moves through the world. In Lumen, there are no hand-placed light sources; if the LED on a piece of tech looks like it glows, it actually is glowing. The fluorescent light fixture casts its cold light into the world simply by looking bright, with no further fakery required. The GI effect of lighting spilling around a space just happens. In this system, iteration is instantaneous. Reader, I cannot stress enough how much this matters for the process of making these onscreen worlds; not only is it tremendously faster to make things look pretty in the first place, every single source of light in the world can move, or change, or be interactive.

However, Lumen and its ilk are still fundamentally shortcuts, and that means the challenges for working with them are still there. With baked lighting, the shortcuts (sometimes called "optimizations") that can be taken to improve real-time performance or squeeze your game into less disk space are fairly harmless; with Lumen, it is, broadly, either a matter of living with a demanding, high quality image, or watching your game world disintegrate into a fizzling Rorschach-inspired fever-dream. It is very demanding on the hardware we use to play games. And this is OK! Every new technological leap goes through growing pains, and when this new approach to lighting is at its best, you never even think twice about it. You need only look at a game like the exemplary Indiana Jones and the Great Circle to find an example of how this can help free up a game to give the player beautiful visuals and lots of interactive stuff at the same time. (Great Circle is not an Unreal Engine game, but it is built using similarly modern technologies).

For me, all this stuff is very neat. In May 2025 I don't work on games for a living. When you get to it, for me this is all just the means to making a pretty picture, and when I sat down to make a new one last night, I was delighted to find how much more quickly I could work. I don't have as much time for creative pursuits these days as I used to, so, fundamentally, Lumen was the difference between actually getting to craft the scene in my head and having to resignedly say, "Oh, I'll get back to this tomorrow and do that bit if I have time." Kudos to the clever people that invented it.

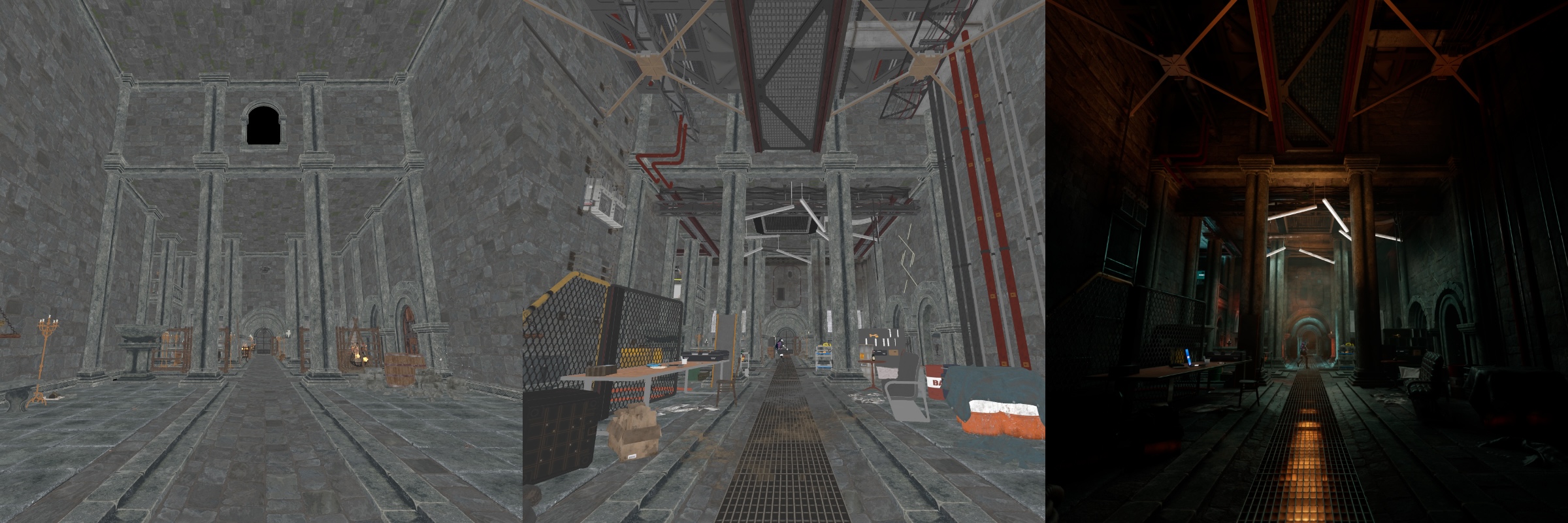

Left to right: Off-the-shelf dungeon asset pack, to fully decorated, to fully lit.

"Underground", May 2025 - Lumen lighting. Gothic meets cyberpunk, sorta. This was fun!

Good to see you again

It's the same resolution as my old one (4K), but it's physically bigger so that I can see the stuff on it a little better without my glasses on (a few years ago, that wasn't an issue). It's a VA panel so it has more vibrant contrast than the IPS panel it replaces, but that contrast gets wonky when you look at pixels at steep angles. To fight this flaw it is curved so that all the pixels are more-or-less pointed at my face when I'm using it. It has a higher refresh rate too, which is nice for a sense of fluidity and let me enjoy a few more frames for every second of gameplay.

It made no difference to how much I enjoyed the game.

Veilguard invites you to be part of a story full of bombast and big ideas, all competently and extravagantly delivered on-screen. As a game it is easy to learn and smooth to play; as a world it is charming, if mildly tedious, to explore. The palette of villains (some old, some new) are enticing, and requisite-for-the-genre companions are broadly likable, each loaded with a unique variety of baggage and personalities all their own. It has been a decade since we last saw a new on-screen adventure set in Thedas and going back is a most welcome excursion.

Veilguard picks up several years after the concluding events of Dragon Age: Inquisition, and while it includes quite a number of returning references and faces from that game's era, many are left behind for better or worse to make way for a new band of well-resourced misfits become their own region's heroes. Tonally it is a little brighter than previous adventures, but not so much as to be unrecognizable, and it does readily descend to grim depths as the plot demands.

Mechanically-speaking, Veilguard is focused and distinctive, giving you a straightforward but highly nuanced way to define your character's growth from disoriented and confused Level 1 Peasant to emotionally damaged and pissed-off Level 48 Demonshredder. I think it actually provides the most competent example of this RPG progression staple to come out under the BioWare name for a long, long time.

I'm not overly fond of Veilguard's Hobbit-esque aesthetic flavor; I think the tone of the game would have been better served by something more grounded. It didn't stop me enjoying the story, but I got the facial proportions 'wrong' (as in, out of line with the rest of the characters) in the character creator a few times. A word to the adventurous: exaggerate your eye, brow, eyebrow, nose, and cheek spacing/qualities at least a little bit. The rest will work out.

Without spoilers: I will both commend BioWare for braving new social territory in their role-playing games, and criticize them for their exploration being too anachronistic. The specifics felt forced in-situ and I am positive they could have found a way to explore the ideas which may have been a bit subtler, but more natural to the residents of Thedas. I hope they try again, and more cohesively, with their next project.

Now, back to the vibe: This is big, swashbuckle-y storytelling, not a subtle tale of intrigue and hard choices. While it is by far at its strongest with bombastic set-pieces, Veilguard does occasionally show an ability to cherish the quiet moments, and these remain my favorite parts of the game. It accomplishes the trademark BioWare feel, and is easily among the best-executed of the studio's catalog. It is, in the most fanciful sense, a role-playing game.

In the context of a computer/video game there are two versions of what the "role playing" part of the term means:

The first is primarily mechanical: You, the player, use complex, interlocking systems to map your imaginative will upon the game world. If you care to, you may maintain a fiction about your character in your head to ground the actions you take within the game world. This is, loosely, how I would categorize the likes of Skyrim or Baldur's Gate 3. Games in this model prize improvisation before everything else.

The second version is primarily imaginative. You, the player, put yourself into the head of a character in this world and use its characters, quests, narrative choices, and conversations to take part in a fantastical story. This is more how I would describe most BioWare games and titles from CD Projekt Red. Games in this model prize active, "on-screen" storytelling and narrative complexity above all else.

Veilguard fits in that second group almost gleefully, and that is, I think, going to remain a point of consternation for anybody comparing it to more improvisational games. As I've gotten older (and my eyesight slightly worse), I've increasingly hoped for games to add new layers of improvised responsiveness and flexibility, letting me poke and prod their worlds in hope that the game might notice and poke me back for once. Instead, much like this new monitor, this game is really just bigger, shinier, and modestly more polished (but not really any more nuanced) than what I've had before.

And that's fine. I can find flaws with it or point to places where I'd hope for more nuance or depth, but I unreservedly enjoyed it. There's nothing wrong with iterating on an idea as long as the execution is good, and Veilguard is rather good where it counts.

The Piano Saga

There's nothing wrong with this. There's an enormous world of music production hardware and software, an awful lot of which is highly accessible to anybody with a moderately powerful laptop, decent set of headphones, and bit of regular disposable income. Endless sonic exploration and construction can fit in a backpack. Digital audio workstation software such as Cubase, Logic, and Studio One are incredible environments for translating the sound in your head into complex compositions that can be refined and tweaked and arranged until you fall asleep over the keyboard at three in the morning, that one not-quite-catchy-enough section stuck in your thoughts.

But while fitting all that in your bag and being able to make music wherever life takes you is a gratifying reassurance, especially in your nomadic years, it had a very particular consequence for my relationship with music: I was spending so much of my "music time" on crafting a better tune, rather than intuitively inventing one. The tools themselves provided so much detail and precision that I was barely spending any time on actually composing music, and spending a heck of a lot more on arranging and shaping what I had put together. When you create and distribute your own work, you're responsible for not just composing and performing/programming it, but also mixing and mastering it, which are lengthy, iterative processes all their own. And now, with my time constrained by work, parenthood, and other hobbies (like making any progress on a third book), I was realistically having trouble even putting together one new piece of music a year, and most of that would be spent on refinement, not improvisation or discovery, which are much more fun.

I decided that this was not the relationship I wanted with music. When I was a kid, up through my teenage years, I was put through piano lessons across a few different teachers. Some of those relationships went better than others (thanks Marcos, sorry Sharon). I wasn't a great pianist, but the soulfulness of the instrument and a plentiful helping of music theory stuck with me. I decided having a piano in the house was the right move to make to rediscover the joy of simply being able to play, without any fiddling or friction.

My home is not large enough for a grand piano, even a small one. It just isn't (UK homes are small). An upright just about made sense - I trawled the Piano World forums for well-liked models. Despite much of the consensus being "Don't ask the internet, try it in person you idiot", there were a few modern models from different brands that seemed to be universally recommended. At the same time I saw some high regard for digital pianos, but having last meaningfully been exposed to the things more than ten years earlier, I was skeptical.

I made my way around a handful of showrooms, and tried out a number of instruments. I learned a couple things:

1) The acoustic upright pianos that I wanted to take home consistently cost 2-3x my budget. I took a real liking to Kawai's lineup (especially the K-200, what a delightfully complex tone) - there was a Danemann that I found pleasant as well. But I have little appetite for negotiating price on something like this, and that part of the experience left me less-than-excited.

2) Digital pianos have (mostly) evolved quite a lot since I last encountered them.

I sampled digital options from Yamaha, Kawai, and Roland. Nord, despite producing very interesting options, was out of the running as they didn't seem to provide the 'furniture appliance' experience, and no dealers within a sane range offered anything from Casio.

Here is my evaluation of the various options:

Yamaha's Clavinova line seemed nice at first glance, but this luster faded quickly. The keybeds were adequate, but the quality of the sample sets and cabinet speakers produced a distinctly artificial tone, a bit muffled at best, flat at worst. Together with controls that evoked a 2003 TV remote vibe, the experiences of the CLP-735 and CLP-745 were not great.

Kawai's 2024 CA series had some interesting quirks. The keybeds were terrific, and the newest sample sets were of a higher quality than what Yamaha had to offer. The cabinet speakers across their lineup ranged from "decent" to "actually rather good". The controls were nearly as clunky as those on the Yamaha offerings. I think if my search had ended there I might have ended up taking home a CA-401 and felt good about it.

But then it was over to Roland. The keybeds were nice, to my fingers maybe a slight step back from Kawai, and the controls seemed a little more intuitive to my eyes. The sound they produced had a distinct 'feel' from the other two brands; the reason for this is that when it comes to piano simulation, the other models available under £2000 rely on complex sample sets (essentially libraries of micro-recordings of real pianos that are triggered and combined in response to the player). Roland's options instead rely on a modeling approach, where the instrument synthesizes a custom piano tone that's tailored to your taste and space. With some easy tinkering it made the instrument feel alive, and that was very interesting.

(I should note that build quality was impeccable across all three manufacturers. When you're paying over a thousand pounds for an instrument you expect it to be well made, and nobody disappointed on this front.)

The emotional, calming delight of communing with an instrument is essential part of the musical experience, and finding it in a digital instrument surprised me. Ultimately I found it in three such digital instruments during my tour, and I took home the cheapest of them: a Roland HP704. The other two - a bigger, more expensive Roland LX model and a significantly more expensive Kawai - were both very nice, but I'd found my sweet spot.

Having lived with it for a little while now, I have notes for the fine people at Roland, but none of true consequence. It's well-made, feels great to play, and has made family and guests pause to indulge in its house-filling sound from even the most random noodling sessions. It can act as a top-notch MIDI controller for those times I want to bring out the laptop. But most of all, it's simply been fun to have a piano right there in the house, ready to bring a dull moment of the day to life with no notice at all. And sometimes I'll catch my kids opening it to dawdle on the black and whites completely unprompted. I can't ask for more than that.